|

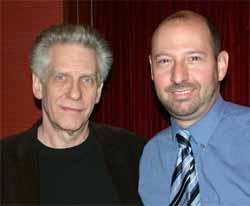

| David Cronenberg & Jonathan Stryker |

One director who needs no introduction to horror fans is David Cronenberg. With a filmography that spans 40 years beginning with his short film TRANSFER and continuing with his most recent work EASTERN PROMISES with Viggo Mortenson and Naomi Watts, this brilliant Canadian filmmaker has carved a niche for himself that has included one dazzling and provocative film after another, simultaneously wowing and repulsing audiences the world over. Mr. Cronenberg is responsible for some of the most unforgettable, iconographic, and genuinely disturbing images ever committed to celluloid, as evinced by the parasitic creatures affixed to Joel Silver’s face in SHIVERS; the phallic parasite growing in Marilyn Chambers’ armpit in RABID; the murderous children in THE BROOD; the malevolent mind-controllers in SCANNERS; the vaginal stomach opening in VIDEODROME; and the game port in eXistenZ to name a few.

David Cronenberg graciously took some time out of his busy schedule to meet with me in October at the posh New York Regency Hotel in midtown Manhattan over a cup of tea to discuss his career. Many thanks to RJ Millard of Focus Features for arranging this interview.

Jonathan Stryker: Was becoming a filmmaker a way of liberating yourself from the difficulties of being a novelist and struggling to find your own voice?

David Cronenberg: Well, that’s an interesting question. The movie thing certainly came in sideways. When I was starting out, the technology certainly intrigued me because I’m a gadget kind of freak. The drama part, you know, working with humans was obviously exciting, as opposed to writing where you’re isolated and spending a great deal of time alone. But, the fact that I could write was very important. There were no scripts around when I started making short films, so you had to generate them yourself somehow. And if you could write, that was a real strength. So, they did kind of blend together, the writing, and it’s only maybe now that I’m beginning to feel that I perhaps don’t have the temperament to be a novelist.

JS: (Laughs) Wow, even after all of these years?

DC: (Laughs) I’m still not convinced totally. And it’s funny because I thought of Ingmar Bergman. When he published his four screenplays he re-wrote them so that they sounded sort of like novels because at that time the novel was still the premier art form, and he felt that movies were a lesser art form. Of course, ironically, he was one of the people who elevated it to the point where film was considered an art form.

JS: True. For that matter, where would Wes Craven be without THE VIRGIN SPRING?

DC: Yeah, so I guess that I haven’t given up the – the things that the novel can do, movies cannot do, and vice versa obviously. So, in a way, I kind of would like to do both. However, the amount of time it would take, you know, to take the years off that it would require to write a novel, that’s difficult for a film director to do in practice. So, whether or not I could ever really do that – you know, it’s a nice fallback should I ever get to the point where the physical aspect of filmmaking would say become difficult because I’m too old or whatever. But at the same time, from what I understand with novelists you need stamina to write a novel as well! Even though it’s not the same thing, there’s an interesting crossover.

JS: One of the most difficult things that a director must decide prior to filming is the placement of the camera. Do you know what you want prior to shooting?

DC: No, I don’t. I totally don’t. I don’t do storyboards. And I find that a strange sort of development which maybe comes from Hitchcock’s mythology that he liked to promote the idea that he did everything himself. But, if you do that, you really are cutting out the collaboration of your actors, really. If you figure out where they are going to stand in a room, before you have even designed a room, or found a location, and haven't cast the actors, it means that you're not – I mean, why cast fabulous actors and then tell them where to stand and how to say the lines? You really want their involvement and their collaboration. They’ll say, “No, maybe I should be lying on the floor instead of standing at the window.” If you don't have that in your storyboards you say, “No! That’ll ruin everything!” So, you end up limiting yourself.

JS: Given the scientific nature of your work, do you ever think of your films as cells, parts of an overall living organism, i.e., an oeuvre? Do you consider yourself an auteur?

DC: Well, I have never thought of my films that way. However, I like that. I like the metaphor and so I accept it, and from now on I will think of them exactly that way!

JS: Do you feel that your lack of Jewish identity during your youth influenced the isolated nature of your films?

DC: Well, I never felt not Jewish. I was pretty Jewish, it's just that I wasn't very religious. And that really separated me from a lot of my Jewish friends who were religious, or at the very least went through the motions of being religious. I went to a high school in Toronto called Harbord Collegiate which was 95% Jewish. The teaching staff wasn't, but the student body was. And it actually was one of the only Jewish schools in Toronto that was shut down for Jewish holidays because there just weren't enough kids there to make it worthwhile to remain open. And I wasn't one of those kids who would have been away, but I was happy to take the time off. I guess it was double alienation, I was alienated from my Jewish friends because I didn’t go to Hebrew school, I didn’t have a bar mitzvah, I didn't do that stuff. But at the same time, I always thought of myself as Jewish. But not really alienated, you know, just different. I didn't feel that as a pressure.

JS: How involved are you in the advertising campaigns of your films?

DC: I do get quite involved, and I am surprised to say that it is often welcomed, interestingly enough. Focus Features and New Line Cinema have been great. They send me everything. We have arguments sometimes. The poster for EASTERN PROMISES was my choice; there were many other posters created for the film and I gave them scathing reports on why they were no good. So, it is definitely is a collaboration. Legally, I have no right to have any input. But on the other hand they need input. It's a difficult thing, I cannot pretend that I am a marketing guru, that’s for sure. It's a real art. But, I can watch the trailers as though I am a spectator and I can tell if it's not telling me something about the real movie. So, I do get quite involved, yes.

JS: What did it mean to you to be inducted into the Canada Walk of Fame as well as being bestowed the Order of Canada?

DC: Well, those are two different levels of things. The Order of Canada is really like the Legion of Honor. It's sort of the highest civilian honor that you can get in Canada. And, it is important to me because when I started making films I was rather scurrilous and considered reprehensible and being on the outside one could certainly take strength from that. But, you don't really want to be considered a bad citizen and so suddenly this is a complete reversal so it does mean a lot, actually.

JS: What are your feelings about home video and how your work has been represented in the different formats?

DC: I love home video. I mostly watch movies at home on DVD. I have the Sony PlayStation 3 primarily to watch movies on Blu-Ray. And I love the fact that you can get true HD over satellite and cable. I'm a bit of a recluse. I don’t mind the solitary or family experience of watching movies at home. I don't miss the group experience of the cinema as much as a lot of other people would. So, I rarely see movies at a theater. If I do, it's almost always my own film at a film festival.

JS: Will TRANSFER and FROM THE DRAIN, as well as your work for television, i.e. “Programme X,” “Peep Show,” “Teleplay,” ever be released on home video, or is there a conscious effort to retain them as much as possible from public view?

DC: Well, TRANSFER and FROM THE DRAIN were never made for television. I was just experimenting to see if I had anything to say, if I had an eye and an ear so to speak. But, I did do some work for television. But TRANSFER and FROM THE DRAIN are both very lumpy. I tend to only let them be seen at film festivals like Rotterdam, for example, is attended by real cineastes, you know, they are interested in it because it's your work. They're not interested in whether or not it’s any good. But in general, I would say that those films are not good enough. But, some of my later works are more interesting. There is a Region 2 Japanese DVD with some of my work (called DAVID CRONENBERG SHORTS, available from Xploited Cinema), it has an episode of "Peep Show" that I did called "The Lie Chair" and an episode of “Teleplay” that I did called "The Italian Machine".

JS: You’ve stated that you weren’t aware of horror films in Canada at the time that you began directing. Bob Clark’s brilliant BLACK CHRISTMAS was released about one month after you wrapped filming on SHIVERS. Were you aware of this horror film at the time?

DC: No, and don't forget that Bob Clark was American, he was from Florida. And we thought of him that way, he was not a Canadian filmmaker. That doesn't mean that he wasn't welcome, and also he did some very interesting things with sound in that movie and we were pretty interested in that, Ivan Reitman and myself, we noticed that stuff. He was using Canadian technicians but not really CBC-TV-type sound, he was doing really interesting movie sound which was very experimental, and yet in a commercial movie, so that was fascinating. But, BLACK CHRISTMAS wasn't really a Canadian film in that sense than, and of course I didn't know that that was going on when I was shooting SHIVERS. Remember, I was in Montréal doing SHIVERS while he was doing BLACK CHRISTMAS in Toronto. And new those are like two separate worlds, really.

JS: STEREO and CRIMES OF THE FUTURE were filmed in some of the strangest and most antiseptic-looking buildings I’ve ever seen. Where was this?

DC: (Laughs) They still exist in Toronto. Scarborough College was a brand-new building at that time. It was practically not even inhabited, it was all poured concrete. It had a very interesting style, and we had some very interesting architects working. And whenever there was a new building going up I was almost always the first one there to see it. I was really fascinated by the question of space. I think that that’s something that you really have to master, it's a surprise. How do you move the camera through space with people moving in different directions and how do you carve out the space? It's not easy actually to do it with style and elegance, as opposed to just going out there trying to get whatever you can get. And so the architecture as the shaper of space before I even got to the location was a crucial element to me, it would draw me.

JS: A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE and EASTERN PROMISES both star Viggo Mortensen, an actor I have liked immensely since first seeing him in CRIMSON TIDE. Do you have any other films in the works with him?

DC: Well, I love Viggo, you know, and I would love him to be in every movie that I make obviously. So, whatever movie project that I am playing with, and I’m toying with several right now, I will always look for a part for him. He's the sort of actor who even if he wasn't the lead role he would still take it.

JS: EASTERN PROMISES boasts a lustrous score by the great Howard Shore, who has scored 12 of your films. Where did you meet him?

DC: Well, Howard is a Toronto boy, and we’ve know each other since we were teenagers. And then he got his gig with Lighthouse, which was a very successful Canadian big band that traveled around the world, and then did Saturday Night Live with another Toronto boy, Lorne Michaels, so Howard was the musical director for Saturday Night Live, and one of the nurses in the All Nurse Band. But, he was always around because we had friends in common and he was a bit older than me.

JS: Thank you so much for your time; I could sit here and talk for another five hours!

DC: (Laughs) OK, thank you.